Learning can take many forms; reading and lectures can both help a student to internalize information. But there are some things that simply cannot be taught solely through classroom exercises. It doesn’t make sense to read about bomb disposal or to learn live fire procedures on a chalkboard. At the same time, it’s even less desirable to have a student practice these things in the real world, at least not the first time out.

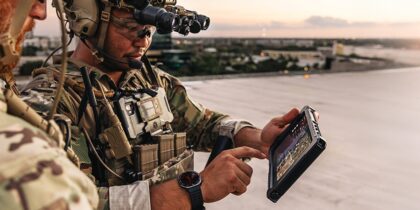

Virtual reality training offers a pragmatic compromise. By delivering an intimate digital experience, students can undergo these military moments firsthand, without risk to themselves or others. In virtual reality (VR), an individual enters a computer-generated simulation of a three-dimensional world, using helmets, gloves and other sensors to interact with this virtual environment.

As a vehicle for education, virtual reality training boasts many advantages over traditional methods. It allows trainers to expose their students to physically intense situations without the risk of actual injury, and it allows a student to replay a scenario until the lesson has been absorbed. It also can be a cost-saver, allowing multiple students to take part in a simulation from different locations at the same time.

Applications of VR

A number of examples have already emerged in which government leaders have directed military units to train using VR:

- Researchers at the U.S. Army Edgewood Chemical Biological Center are using VR to train soldiers on a complex piece of detection equipment called the Husky Mounted Detection System, or HMDS. This tool detects underground explosives and anti-tank mines.

- The U.S. Air Force has used VR to simulate a medical transport from Bagram Airfield in Afghanistan to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany under the care of a Critical Care Air Transport Team, delivering (virtual) emergency medicine, while honing the critical care skills of physicians, nurses and respiratory therapists.

- British military recruiters are using VR as a recruiting tool, dropping potential recruits into virtual battlefield scenarios where they drive tanks and engage in live fire exercises.

Beyond military uses, NASA planners are putting VR to work preparing astronauts for space walks. VR offers astronauts a chance to learn how to return to their spacecraft should they become untethered, while also offering lessons on how to control the space station’s robotic arm and manipulate payloads in zero gravity.

A Ready Audience

Military educators should find a ready audience for this type of training. The young people who typically make up the newest recruits are accustomed to functioning in virtual worlds, thanks to their typically deep immersion in video games.

This comparison isn’t perfect, however. Video games don’t offer the depth of experience or the tangible, hands-on sense of a VR training session. When it comes to federal and government uses, especially military maneuvers, “people can talk about it until they are blue in the face, but, until you try it in some way, you can’t really understand,” says Henry Stuart, CEO of virtual content developer Visualise. Still, there are similarities, especially in the translation of an on-screen engagement to a visceral, personal experience.

More to the point, VR is becoming an increasingly common form of consumer entertainment. Many of tomorrow’s recruits likely will have had direct experience wearing the helmets and manipulating the objects that make up the virtual world. Research firm MarketsandMarkets predicts that demand for VR (and its close cousin, augmented reality) will reach $1.06 billion by 2018.

Cost factors may help drive this high adoption rate. At market research firm CCS Insight, Chief of Research Ben Wood predicts that by 2018, 90 percent of all VR headset sales will be along the lines of the Samsung Gear VR — inexpensive devices powered by smartphones.

Why is the military increasingly turning to VR as the training vehicle of choice? Much of the answer simply comes down to risk. There are some things — live fire, bomb disposal and medical evacuation — that they’d rather not have trainees learning in the field.